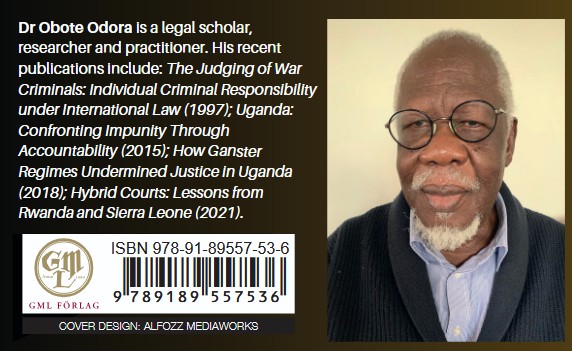

New Book by Obote Odora is a Magnum Opus on Uganda’s Colonial Legacies and Postcolonial Tyranny

The Ghost of Empire: How British Colonialism Forged a Nation of Shadows

Uganda, as meticulously dissected in Betrayal and Dependency, is not a nation born of organic cultural consensus but a fabricated geopolitical contraption stitched together by imperial decree. With surgical precision, Dr. Obote Odora exposes the skeletal architecture of colonial control—the 1900 Buganda Agreement and the 1902 Order-in-Council—legal instruments that codified racial hierarchy and economic pillage into the DNA of Uganda’s governance.

Odora deconstructs the myth of benign imperialism, revealing instead a system that rendered Ugandans mere “possessions” under British law, devoid of agency and humanity. Through legal exegesis and historical contextualisation, he demonstrates how colonial laws were less about justice and more about jurisprudential cover for theft, indoctrination, and spiritual subjugation. In this masterful historiographic reckoning, the author contends that British colonialism was less a civilising mission and more a theatre of calculated dehumanisation—its legacy still deeply embedded in Uganda’s contemporary political psyche.

Missionaries, Mis-education, and the Manufacturing of Black Collaborators

Odora’s analysis is particularly searing when applied to the educational institutions of colonial Uganda, which he portrays not as sanctuaries of enlightenment but as ideological factories that produce docile intermediaries for the empire. Christian missionaries, lionised in popular narratives, are recast here as intellectual mercenaries—the vanguard of a cultural scorched-earth campaign aimed at the erasure of indigenous epistemologies.

In eloquent prose and with scholarly conviction, Odora shows how the colonial classroom was not a space of learning but of unlearning—unlearning self-worth, history, language, and cosmology. The product of this curriculum was the mission-educated black intellectual: a culturally amputated figure who speaks the Queen’s English but cannot articulate the aspirations of his own people. These elites, groomed to see their own communities through the eyes of their colonisers, would become the custodians of post-independence despotism—governing not with the people, but over them, and in the service of the very structures that once enslaved them.

From Paper Independence to Puppet Sovereignty: The Anatomy of ‘Donor Democracy’

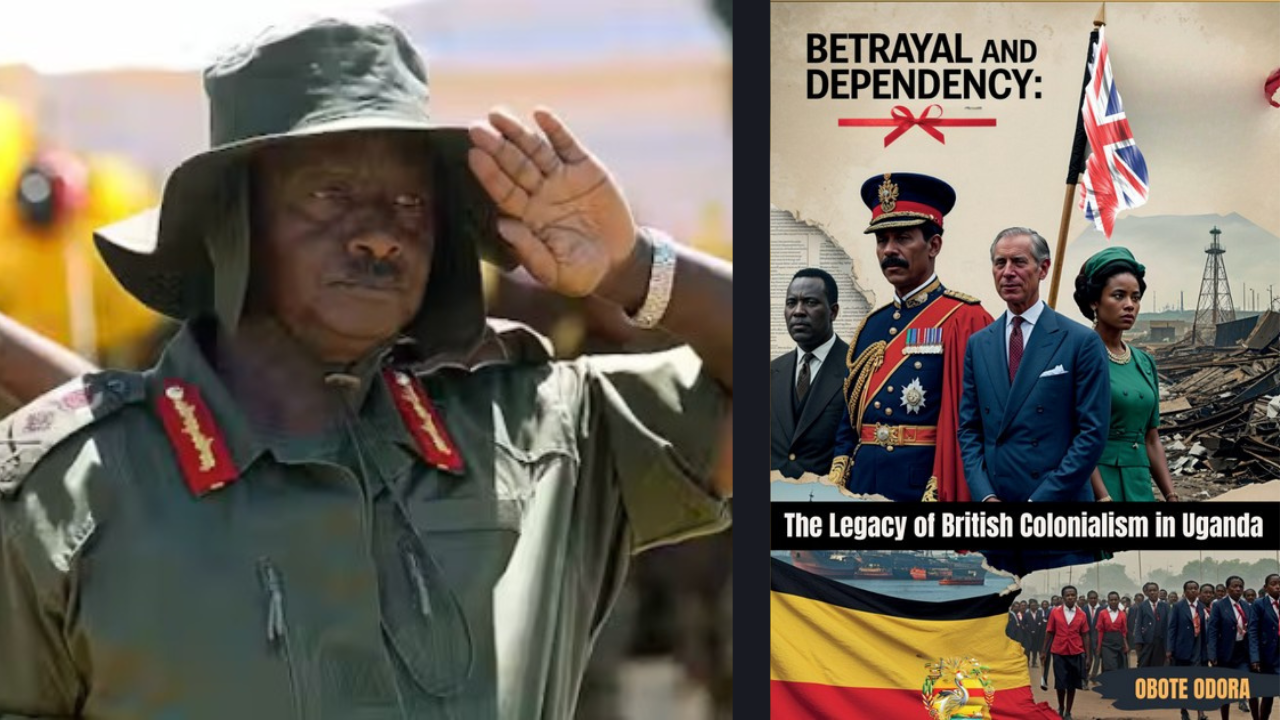

What Uganda achieved in 1962, Odora asserts, was not true independence but a choreographed transfer of administrative instruments from white hands to black gloves. With incisive legal analysis, he unearths the theatricality of the Lancaster and Marlborough House negotiations, showing how Uganda’s so-called Independence Constitution was less a charter of freedom than a coded continuity of colonial power. Odora coins the term “donor democracy” to describe the postcolonial state—a regime ostensibly independent but effectively tethered to Western donors who use elections as façades for legitimacy while maintaining imperial leverage.

More precisely, Odora illustrates how successive Ugandan regimes—from Obote to Amin to Museveni—have danced to the rhythm of foreign funding while orchestrating a domestic symphony of state violence, repression, and corruption. The book unearths this grim paradox: that Uganda’s sovereignty is performative, its elections ritualistic, and its leaders unaccountable to the people but eternally beholden to international financiers and neo-imperial benefactors.

The Dictatorship of the Intellectuals: How the Educated Elite Became the New Colonisers

Perhaps the most damning revelation of Odora’s magnum opus is the complicity of Uganda’s own intellectual class in perpetuating postcolonial oppression. These black elites, graduates of colonial mission schools, are portrayed not as liberators but as parasites—feeding on the state while draining its moral lifeblood. Drawing upon thinkers such as Aime Césaire and Amilcar Cabral, Odora frames the Ugandan intellectual as a tragicomic character: trained to serve the empire, stripped of ideological integrity, and endlessly transfixed by Western approval.

This “dictatorship of the intellectuals” is characterised by legal impunity, moral decay, and an almost religious devotion to state-sanctioned violence. The executive, parliament, judiciary, and military become theatres of this intellectual betrayal, each performing its role in a farcical drama of democracy, while the real plot—resource extraction, elite accumulation, and mass disenfranchisement—plays out behind the curtain. Odora’s prose here is both elegiac and scathing, a eulogy for lost potential and a battle cry for national rebirth.

A Republic of the Forsaken: The People as Hosts, the Elites as Parasites

In one of the book’s most haunting metaphors, Odora likens the Ugandan masses to “hosts” and the ruling elite to “parasites”—a biological analogy that crystallises the exploitative nature of the postcolonial social contract. The peasants, labourers, and forgotten poor—those who till the land, build the roads, and sustain the economy—are perpetually sacrificed on the altar of elite comfort. And yet, Odora does not leave the reader in despair. He insists that history is not destiny and that the narrative can be rewritten if the people reclaim their agency.

The writer’s closing chapters are a clarion call for intellectual decolonisation, civic courage, and moral insurgency. With a deep reverence for Uganda’s cultural wealth and spiritual resilience, he urges a return to indigenous values, grassroots education, and people-powered politics. The book’s final verdict is unflinching: Uganda will remain a pseudo-republic until the dictatorship of the intellectuals is dismantled, root and branch, by a citizenry awakened to its own power.

A Book That Dares the Reader to Think and Act!

Obote Odora’s Betrayal and Dependency is not merely a book; it is an epistemological rupture. It disorients, interrogates, and inspires. With literary elegance and forensic intellect, Odora eviscerates the convenient mythologies of nationhood, governance, and independence, laying bare the raw mechanics of power. This is a book fit for any university library, a required text for students of African history, postcolonial studies, and legal philosophy. More than that, it is a mirror held up to a nation in denial—a sobering reminder that until the past is reckoned with, the future remains hostage to it.

Needless to say, the publication is a landmark work of intellectual provocation and historical reclamation. In a world increasingly sanitised by platitudes and political correctness, this book is a provocation—unapologetic, rigorous, and incandescent. It deserves to be read not once but repeatedly, discussed not quietly but loudly, and acted upon not someday, but now.

Okoth Osewe